According to one of our preferred musical sources:

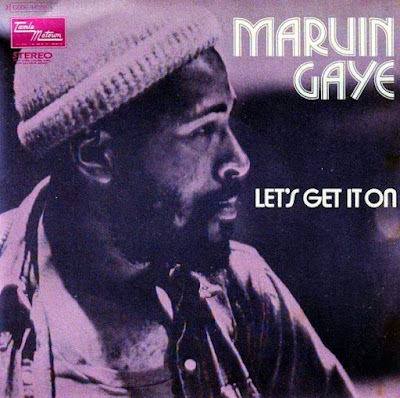

Marvin Gaye – “Let’s Get It On”

HIT #1: September 8, 1973

STAYED AT #1: 2 weeks

“Let’s Marvin Gaye and get it on.” That’s how Charlie Puth and Meghan Trainor — two singers who will end up in this column — described the act of fucking on “Marvin Gaye,” a cutesy retro-pop single that was a minor pop hit in 2015. (“Marvin Gaye” peaked at #21, so I don’t have to rate it.) I’m sure they didn’t mean it that way, but they effectively transformed the name of Marvin Gaye, one of the giants of American pop music, into a goofy joke-verb. This was a ridiculous thing to do, but it’s also part of a larger pattern.

There is, I think, a prevailing cultural view of Marvin Gaye as a sex-music guy, a master of baby-making music. I don’t like this line of thinking. Marvin Gaye was too good for that. Through the ’60s, Gaye was a master of the kind of formalist pop-soul that Motown was cranking out — one of the brightest stars in a galaxy full of them. And after he’d perfected that, he helped pioneer politically righteous soul music, showed what a pop musician could do when he wrested artistic control away from his bosses, and created a pretty amazing and mostly instrumental orchestral-funk score for a not-great movie. And then he got around to making sex-music. Then, after that, he wrenchingly chronicled his own divorce, made one of history’s most graceful pivots to disco, and proved to be the first ’60s icon capable of understanding what an 808 could do. He did all of this by the age of 44, when his own father murdered him. That is one of the all-time great legacies — an artistic life much too rich and varied to become a verb.

But I think the “Marvin Gaye” view of Marvin Gaye also gets something else wrong. It undersells “Let’s Get It On,” the 1973 sex-music masterpiece that probably remains Gaye’s best-known work. “Let’s Get It On” is a deep, heady zone-out of a song, one that looks for, and finds, the divine in the physical. It’s a song about a feeling that Gaye had to struggle and fight to find, one that changed his life once he found it. It’s an amazing song, but it’s also more than that.

In the liner notes of his Let’s Get It On album, Gaye felt the need to justify the fact that he’d just made a whole album about sex, an album with a song called “You Sure Love To Ball.” There’s something lovably awkward about what Gaye wrote in his own liner notes: “I can’t see anything wrong with sex between consenting anybodies. I think we make far too much of it. After all, one’s genitals are just one important part of the magnificent human body.” (Marvin Gaye was better at writing songs that he was at writing non-song things.)

Gaye probably wrote that justification, at least in part, because even in 1973, people generally weren’t singing that explicitly about sex. (They definitely weren’t releasing songs called “You Sure Love To Ball.”) But he also wrote it because he’d just figured out how much he could enjoy sex, and he was still processing that. Marvin Gaye, Sr. — Gaye’s father and eventual murderer — was a minister and a religious fanatic. He abused Gaye physically and psychologically throughout his childhood, and Gaye spent decades fighting the guilt he felt over the idea of sex. He had a whole lot of deeply ingrained hang-ups, and the chaos of his own life had to make them even worse.

“Let’s Get It On” was Gaye’s second #1 hit, and it came five years after “I Heard It Through The Grapevine,” his first. Gaye had been depressed after the success of “Grapevine,” a success he wasn’t sure he’d earned. He was also depressed about Tammi Terrell, his old duet partner. One night in 1967, Gaye and Terrell were performing together at a Virginia college when Terrell collapsed into his arms. It turned out that she had a brain tumor, and she died in 1970. It crushed Gaye. Also, Gaye’s brother was fighting in Vietnam, writing him letters about all the horrors over there. It was almost too much. Gaye considered temporarily quitting music to try out for the Detroit Lions. Instead, he made What’s Going On, the album that changed everything.

What’s Going On, quite possibly the greatest soul album ever recorded, is a deep and heavy exploration of the mind of a guy watching society fall apart around him. Motown boss Berry Gordy, who was also Gaye’s brother-in-law, refused to release the title track as a single; he was worried that a political song like that could alienate the label’s white audiences. But Gaye went on strike until Gordy agreed. The song was huge, peaking at #2. (It’s a 10, obviously.) With its success, Gaye demanded creative control over the album. The album was huge, too, and it landed two more singles in the top 10. (“Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” peaked at #4, and “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)” peaked at #9. They’re both 10s.)

What’s Going On won Gaye a new contract, with more money and total creative control. But it did not calm the chaos of Gaye’s life. Gaye’s anti-Nixon song “You’re The Man” flopped, and Gaye scrapped the album he’d planned to release around it, possibly because of further arguments with Gordy. (That album only just came out last month.) Gaye’s marriage to Berry Gordy’s sister Anna, who was 17 years older than him, was falling apart. When Marvin’s son Marvin III was born in 1966, Anna had faked a pregnancy; the real mother was Anna’s niece Denise. Anna accused Marvin of abusing her and cheating on her, and he accused her of the same things. They finally separated in 1973, two years after they’d moved to LA together. (Later they’d divorce, and that divorce would be the subject of Here, My Dear, Gaye’s 1978 album.)

Marvin, newly single, had fallen head-over-heels for Janis Hunter, the 17-year-old daughter of his friend Slim Gaillard, a jazz musician. (Gaye and Hunter got married in 1977, when they already had two kids together, and they divorced four years later.) Gaye was already recording the Let’s Get It On album when he and Hunter got together, so she probably didn’t directly inspire the song. I would guess that the same impulses that drove Gaye to Hunter — the same needs — are the same ones that led him to record “Let’s Get It On.”

In any case, Gaye was dealing with a lot. He wasn’t sure how to turn those struggles into music. It took time. “Let’s Get It On” had started out as a song by Ed Townsend, a former doo-wop singer whose 1958 song “For Your Love” had peaked at #13. Townsend, who ended up co-producing Let’s Get It On with Gaye, had just finished rehab for alcoholism, and “Let’s Get It On” started out as a religious song. Gaye’s collaborator Kenneth Stover co-wrote the song and turned it into something political, and Gaye recorded that version. But Townsend didn’t like that version of the song. He convinced Gaye that it was really a song about love. He and Gaye got together to rewrite the lyrics again, and “Let’s Get It On” is what came out.

“Let’s Get It On” is a plea, a statement of need. Its famous opening — “I’ve been really tryyyyyyin’, baby/ To hold back these feelings for sooooooo long” — isn’t theater. It’s strained and raw, Gaye really admitting that he’s been fighting his own urges. And when he sings about sex being OK, it almost sounds like he’s convincing himself just as much as his partner: “We’re all sensitive people with so much to give … There’s nothing wrong with me loving you/ And giving yourself to me can never be wrong if the love is true.”

In another singer’s hands, some of these lines — “you don’t have to worry that it’s wrong” — could be oily, creepy. It could come off like the drunk frat boy in Heathers who tries to convince Winona Ryder to fuck by quoting Marvin Gaye to her. (Different song, but still.) But in the way that Gaye sings it, he lets his own internal struggle hang in the air. Parts of “Let’s Get It On” sound absolutely effortless, Gaye’s falsetto floating over everything else like a gull on the breeze. Parts of it are raspy and intense and feverish. In Gaye’s hands, it becomes a gospel song, an urgent devotional. Gaye even spells that out with his word choices: “Girl, you give me good feeling/ So good, something like sanctified.”

Musically, “Let’s Get It On” is a radical departure from the linear, focused pop music that Gaye had made all through the ’60s. Even more than the music on What’s Going On, it’s hazy and miasmic, a love-stoned meditation. There’s a bit of doo-wop in the melody, and it’s easy enough to imagine a clean, spare two-minute version of “Let’s Get It On.” But instead, Gaye turns it into a deep-funk throb.

Gaye multitracks his own vocals — something that nobody else was really doing at the time — and transforms his own voice into a kind of psychedelic blanket, all these different ad-libs riffing away at the same time. And the Funk Brothers — the same studio musicians who had done such great things on his more conventional pop songs — stretch all the way out and ease into it. If you’ve heard the song enough times, the wah-wah guitar notes that open it can hit as a pavlovian signal. But there’s a whole lot more going on: The slow-burbling bass, the angelic strings, the lost peals of saxophone, the wandering flute-tootles. I cannot possibly say enough good things about the drums, those perfect in-the-pocket fills and cymbal-splashes. Even the handclaps sound the exact right way and come in at the exact right time.

The song is a marvel of engineering, arrangement, production, performance, everything. It’s a delicate symphony. And if “Let’s Get It On” has to be the one song that dominates public perception of Marvin Gaye — the one that turns his name into a verb — then at least the one song is a masterpiece, a fucking great fuck-song.

GRADE: 10/10

BONUS BEATS: More than any single scene, Jack Black probably owes his movie stardom to the moment at the end of 2000’s High Fidelity where he enthusiastically covers “Let’s Get It On.” Here’s that:

BONUS BONUS BEATS: There are so, so many rap songs that sample “Let’s Get It On” — here, look — but let’s limit ourselves to one. Here’s Juelz Santana and Cam’ron rapping over a “Let’s Get It On” sample on Santana’s Heatmakerz-produced 2003 track “Let’s Go”:

(As a lead artist, Santana’s highest-charting single is 2005’s “There It Go (The Whistle Song),” which peaked at #6. It’s a 6. But Santana guested on one song that will appear in this column. And he and Cam’ron both rapped together on two Cam songs that ended up in the top five in 2002. “Oh Boy” peaked at #4, and “Hey Ma” peaked at #3. They’re both 10s.)” – Stereogum.com