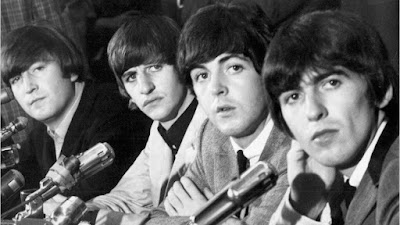

In today’s Legends in Musique!

“Hey Jude” sums up the Beatles’ turbulent summer of 1968 — a tribute to their friendship, right at the moment it was starting to fracture. The single was a smash as soon as they released it on August 26th, 50 years ago — their biggest hit, topping the U.S. charts for nine weeks. It’s the Beatles at their warmest, friendliest, most open-hearted. John, Paul, George and Ringo sound utterly in sync, building to that power-drone “na na na na” chant. Yet it’s a song born from conflict. Nobody knew they were falling apart — in fact, “Hey Jude” was released four days after Ringo officially quit the band, walking out on the White Album sessions. Paul wrote it during John’s divorce, to cheer up his mate’s five-year-old son. As Julian Lennon recalled, “He was just trying to console me and Mum.” The world has been taking consolation from “Hey Jude” ever since.

It’s one of very few Beatle songs about a conversation between men — and like “She Loves You,” it’s a conversation where one friend is urging the other to do right by a woman. (Neither Paul nor John really cared what men had to say about anything — that was one of their deepest spiritual connections.) George Martin fretted the radio wouldn’t play a seven-minute single. John’s reply: “They will if it’s us.” A classic statement of fabulously bitchy Beatle arrogance — yet the word “us” really jumps out of that line. “Hey Jude” is the sound of the lads working hard to capture that feeling of “us,” after it stopped coming easy.

Back in May, John and Paul made a surprise appearance on The Tonight Show, during a brief NYC jaunt. The interview was a fiasco — guest host Joe Garagiola had barely any idea who they were. But there’s a revealing moment, about four minutes into a truly painful chat. Garagiola asks, “The four of you, socially, are you that close?” Paul and John say “yeah” simultaneously — Paul says it twice, while John adds, “We’re good friends, you know.” They’re totally blasé about it — just giving basic background info to this clueless American rube, as if they’re telling him where Liverpool is or how many films they’ve made. To them, it’s obvious. Nothing to get hung about.

But just a couple of weeks later, John had blown up his marriage, his family, every detail of his life. They would never have a simple answer to that question again.

That’s where “Hey Jude” comes from. It’s a moment of fellowship the Beatles had to earn, after a decade when that bond had been the most reliable constant in their lives. Right up to the spring of 1968, John, Paul, George and Ringo were four mates who wanted to spend as much time together as possible, even when they weren’t working. (They’d just gone to India on retreat with the Maharishi.) John was the one who depended most on the other three emotionally. He rarely spoke to anyone outside the band. As he said in 1967, “We understand each other. It doesn’t matter about the rest.” But right after that New York visit, John made a few drastic changes — like walking out on his wife and child, the morning after his first night with Yoko Ono. (Cynthia came into the kitchen and found the two of them eating breakfast. Good morning, good morning.) The others no longer saw him without Yoko around, not even in the studio. His drug intake escalated. This bird had flown.

Like everyone else, Paul was blindsided by the sudden changes in John, and “Hey Jude” was his direct response. He composed it in his head while driving his Aston Martin out to visit Cynthia and Julian, at the Weybridge house where he used to join his partner for afternoon writing sessions. He brought Cynthia a red rose. Nobody else from the Beatles camp was speaking to her. But as Paul reasoned, “We’d been very good friends for millions of years and I thought it was a bit much for them suddenly to be personae non gratae and out of my life.” He also arrived with a tune to sing for Julian, who was only five. That’s just one of the countless weird things about this song — it’s impossible to imagine any other Sixties rock star choosing to spend his day off this way, checking in on his bandmate’s abandoned wife and kid. But that’s just more proof there’s only one Paul McCartney.

Paul was used to dreaming up songs on the road to Weybridge (“Eight Days a Week” for one, “Drive My Car” and “Paperback Writer” as well), but this occasion was different. As he recalled in his 1997 bio Many Years From Now, “I started with the idea ‘Hey Jules,’ which was Julian, don’t make it bad, take a sad song and make it better. Here, try and deal with this terrible thing. I knew it was not going to be easy for him. I always feel sorry for kids in divorces.” He knew the pain of losing a parent as a little boy. “He’d been like an uncle to him,” John recalled years later. “Paul was always good with kids.”

Back in London, at the piano in his Cavendish Avenue bachelor pad, he played it for John and Yoko. When he got to the line “The movement you need is on your shoulder,” he told them, “I’ll change that, it’s a bit crummy.” John replied, “That’s the best line in it!” John heard this new tune as Paul cheering him on in his romance with Yoko. “I took it very personally,” John told Rolling Stone in 1968. “‘Ah, it’s me,’ I said. ‘It’s me.’ He says, ‘No, it’s me.’ I said, ‘Check. We’re going through the same bit.’ So we all are.”

Through the years, in all his sniping about Paul, John never hid his admiration for “Hey Jude.” “I always heard it as a song to me,” he told Playboy’s David Sheff in 1980, shortly before his death. “The words ‘go out and get her’ — subconsciously he was saying, ‘Go ahead, leave me.’ On a conscious level, he didn’t want me to go ahead. The angel in him was saying, ‘Bless you.’ The devil in him didn’t like it at all because he didn’t want to lose his partner.” Paul was going through his own turmoil, splitting with fiancée Jane Asher. He couldn’t stop thinking about this woman he’d met during that NYC visit in May — an American photographer named Linda Eastman. In September, he called and invited her to London. They remained inseparable for the next 30 years, until she died of cancer in 1998. He and John had both found their “someone to perform with” — female artists they not only married but collaborated with musically.

“Hey Jude” wasn’t easy to record — the first time they tried it, Paul and George had a furious argument over the guitar part. When they cut the final track on July 31st, Paul started without glancing back to notice that nobody was at the drum kit. Ringo was in the bathroom. “‘Hey Jude’ goes on for hours before the drums come in and while I was doing it I suddenly felt Ringo tiptoeing past my back rather quickly, trying to get to his drums. And just as he got to his drums, boom boom boom, his timing was absolutely impeccable.” (Ringo enters at the 50-second point.) Paul took the mishap as a good omen. “When those things happen, you have a little laugh and a light bulb goes off in your head and you think, ‘This is the take!’ And you put a little more into it.”

Paul was right — that was the take, the version you hear on the finished record. The Beatles’ biggest hit is the one they started playing while Ringo was in the can.

There’s something else you hear in “Hey Jude,” if you listen close — as the final verse kicks off, at the line “The minute you let her under your skin,” Paul misses a cue and mutters, “Whoa, fucking hell!” They did their best to hide it, mixing it as low as they could, but you can hear it at the 2:58 point — yet it just comes across as excited Beatle banter, the boys calling to each other in the heat of making music. Paul is playing the most hallowed piano in rock & roll history — the Bechstein at London’s Trident Studios. You’ve heard this same piano on countless songs — it’s the one Freddy Mercury plays in “Bohemian Rhapsody,” the one Elton John plays in “Levon,” the one Rick Wakeman plays in David Bowie’s “Life on Mars?” But Paul gets his own sound out of it here.

They made a video on September 4th, the famous clip where the audience gathers around the piano to sing along. It was a reunion of sorts: the return of Ringo. After he quit on August 22nd, he escaped to the Mediterranean, hiding out with his family on Peter Sellers’ yacht, until the boys tracked him down and bombarded him with telegrams saying “You’re the best drummer in the world.” He rejoined in time for the video shoot; the next day, he went back to work on the White Album at Abbey Road.

If you’re looking to make the case that Ringo really was “the best drummer in the world,” you couldn’t top “Hey Jude” as your Exhibit A. His fills are the heartbeat of the song, thumping in communion with the vocalist like he does in “A Day in the Life,” “God” or “Long, Long, Long.” As he once said, “I only have one rule and that is always play with the singer.” Paul, John and George did their most eloquent thinking-out-loud with Ringo providing the pulse. “Hey Jude” wouldn’t groove without him, a major reason why cover versions seem limp. The big exception is Wilson Pickett’s rendition, with Duane Allman on guitar — Muscle Shoals rhythm master Roger Hawkins anchors it, proving “Hey Jude” is a drummer’s song as much as a singer’s.

Cynthia and Julian thought “Hey Jude” was for them. John heard it as the ballad of John and Yoko. But neither side was wrong — countless people around the world have heard this homily speaking to them. “The movement you need is on your shoulder” — John was so right about that line, and as Paul says, he thinks of John every time he sings that part. “Hey Jude” is a tribute to everything the Beatles loved and respected most about each other. Even George, who plays the most low-profile role in this song, tipped his cap with the na-na-na-na finale of “Isn’t That a Pity,” which you can hear as a viciously cheeky parody, an affectionate tribute or (most likely) both. The pain in “Hey Jude” resonated in 1968, in a world reeling from wars, riots and assassinations. And it’s why it sounds timely in the summer of 2018, as our world keeps getting colder. After 50 years, “Hey Jude” remains a source of sustenance in difficult times — a moment when four longtime comrades, clear-eyed adults by now, take a look around at everything that’s broken around them. Yet they still join together to take a sad song and make it better.” – RollingStone.com