Look at him. He’s beautiful. He glows. He radiates splendor. Everything seems to

poof out from him: Hair, scarves, teeth. He makes denim-jacket sleeves look

somehow floofy. This young man comes off like an 18th-century French nobleman

who escaped the guillotine in a time machine, then tried to give himself a

makeover at a biker bar. He smiles constantly. He jukes and spins and shimmies.

He sidles up to bandmates so that they can sing into mics together. He twirls

his mic stand like a majorette. He demands attention, and he rewards it.

Before this young man came along, hard rock was not the kind of thing that

traditionally made a dent on the pop charts. The big metal bands sold

millions of albums, and they filled arenas all across the world, but radio

stayed away. The conventional wisdom was that listeners would hear a loud

guitar crunch, and they’d get nervous or annoyed. They’d switch stations.

Couldn’t have that. Van Halen, the biggest band in the genre, managed one

crossover chart-topper, but they had to synthify their sound to do it. The

rockers got one or maybe two radio stations in every market, but the pop

stations stayed away. Jon Bon Jovi changed all that.

It probably helped that Jon Bon Jovi was not, strictly speaking, a rocker.

His band definitely wasn’t a heavy metal band. They were too bright, too

synthy, too cuddly. But they presented themselves as a metal band, and the

metal audience helped them break through. (In the ’90s, when it stopped

being expedient to present yourself as a metal band, Bon Jovi promptly

stopped doing it, and they enjoyed sustained success that most of their

peers couldn’t match.)

Bon Jovi’s manager Doc McGhee, a former drug smuggler who also handled

Mötley Crüe’s affairs, sent Jon Bon Jovi out on the road with bands like

KISS and the Scorpions, convincing the young man that he needed the

loyalty of the hard-rock crowd. Bon Jovi had seen himself as more of a

Bryan Adams type, and that’s mostly how he sounded. But those metal tours

put Bon Jovi on stages in front of huge crowds and gave his band just a

hint of danger. Once Bon Jovi finally broke through, it was all over. The

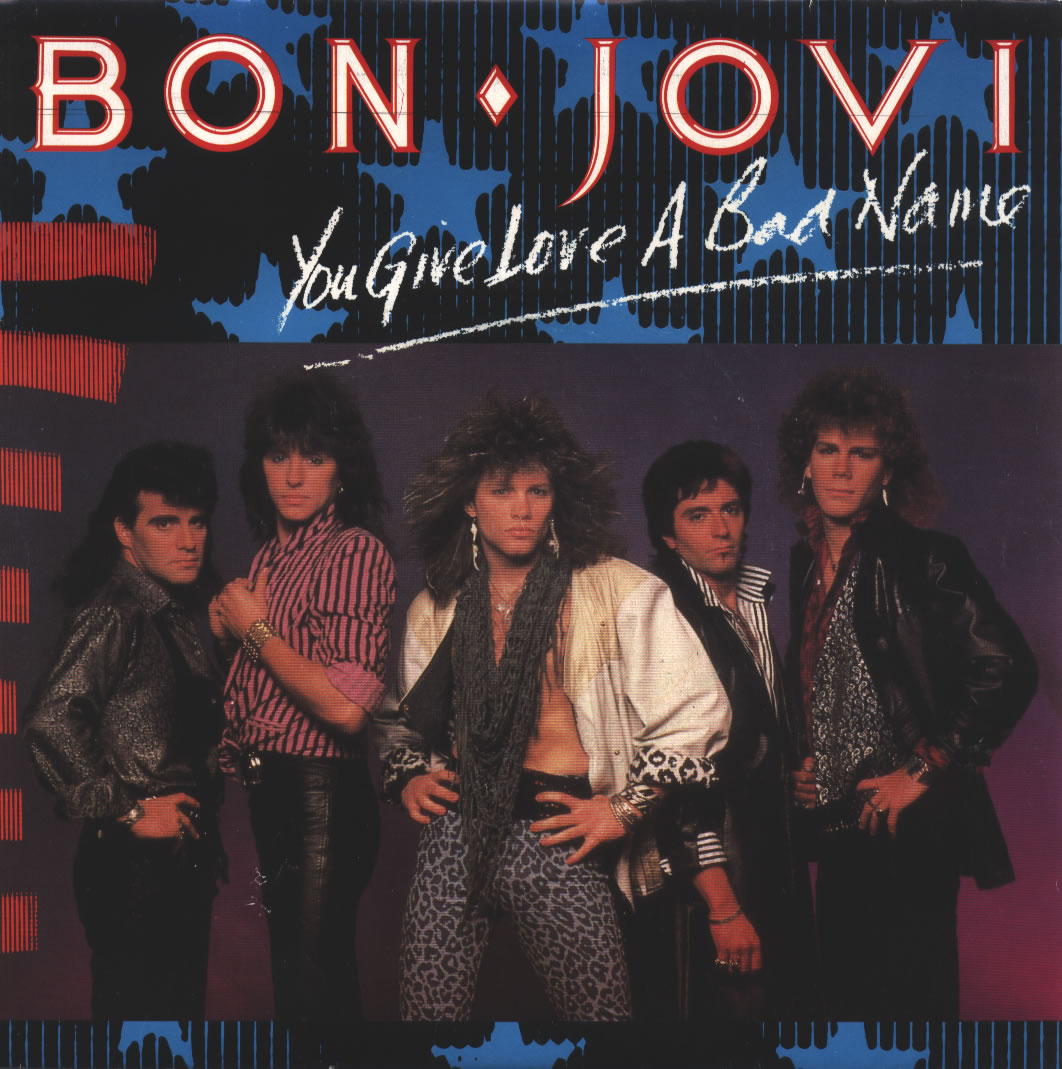

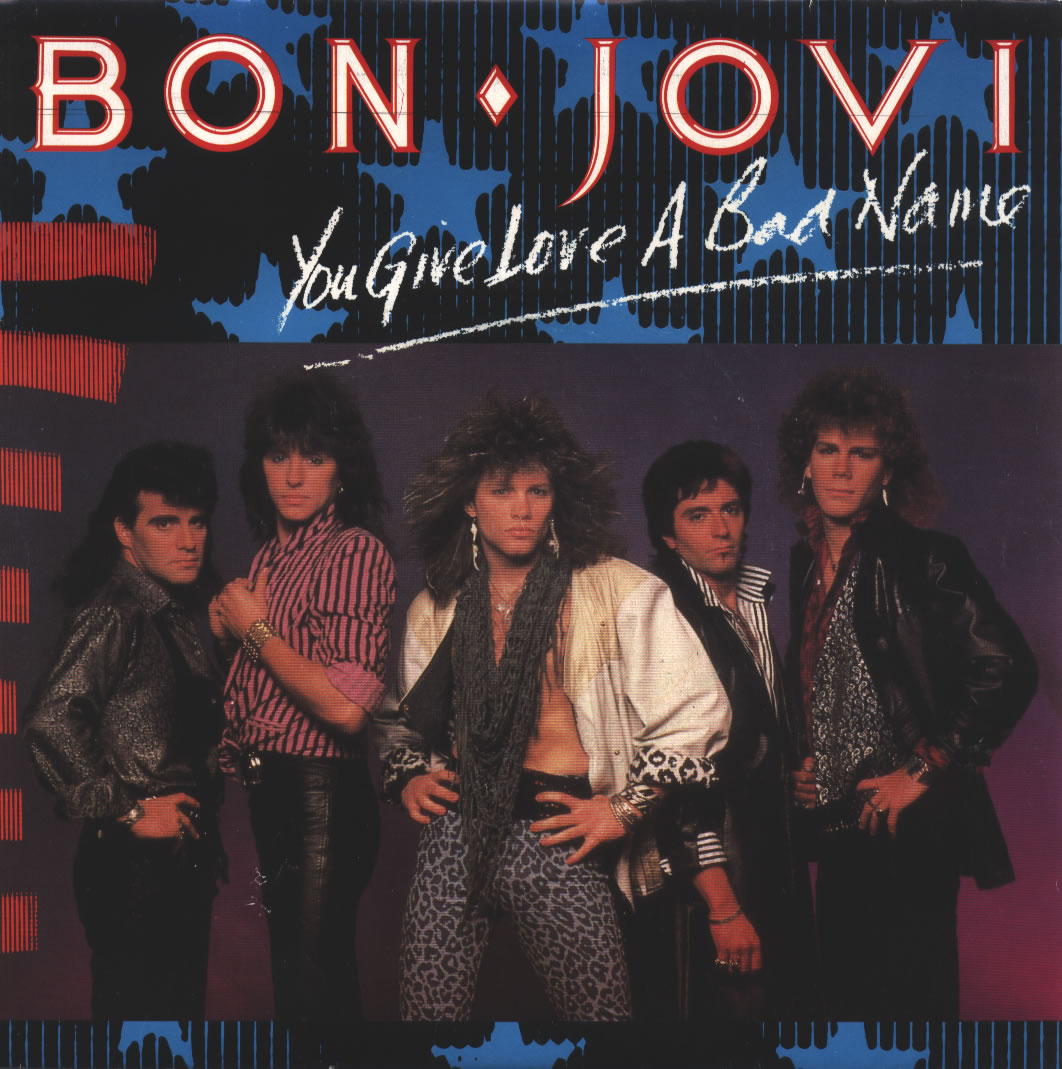

landscape changed. “You Give Love A Bad Name” is one of the most

consequential hits in the history of the Billboard charts. Soon after it

landed, the glam-metal deluge began.

It took a lot of work to get Bon Jovi to that point. John Francis Bongiovi

Jr. came from working-class New Jersey. He’s the son of two parents who

had served in the Marines before becoming, respectively, a barber and a

florist. (The #1 song in America when Bongiovi was born was Gene

Chandler’s “Duke Of Earl.”) Bongiovi started playing guitar and piano

young, and he had a band by age 13. In his teenage years, Bongiovi fronted

Jersey bar bands — Atlantic City Expressway, John Bongiovi And The Wild

Ones, the Rest — and he cut demos of his songs.

Where those demos were concerned, Bongiovi had some good luck. Bongiovi’s

cousin Tony was a producer in New York. He was one of the people behind

the Power Station, the studio where people like Chic recorded. Tony

produced classic records for bands like the Ramones and the Talking Heads,

as well as Meco’s novelty-disco 1977 chart-topper “Star Wars Theme/Cantina

Band.” Tony got a teenage John a job at the Power Station. John swept

floors and made coffee, and he got to record his own demos. Sometimes,

famous musicians — Billy Squier, the E Street Band’s Roy Bittan — helped

out on those demos. John got experience, too. At 16, he made his on-record

debut, singing on another Meco Star Wars tie-in called “R2-D2, We Wish You

A Merry Christmas.”

Labels turned down John Bongiovi’s demos, but a Long Island radio station gave Bongiovi a foot in the door. The station had a contest for local unsigned bands. The guys at the station convinced Bongiovi to enter his song “Runaway,” and the song won. Soon afterward, other stations started playing “Runaway,” too. That got the attention of Mercury Records. Bongiovi signed, and he immediately anglicized his name, becoming Jon Bon Jovi. He also chose Bon Jovi as his band name, following the Van Halen example. And he recruited New Jersey guitarist Richie Sambora, who was three years older than Jon and who had already toured as an opener for past Number Ones artist Joe Cocker. “Runaway” came out in 1984 and peaked at #39.

For their first three years, Bon Jovi were strictly an opening-act band. Their first two albums sold decently. A few more singles charted, though none did better than “Runaway.” One night, while Bon Jovi were on tour with Kiss in Europe, frontman Paul Stanley suggested that Bon Jovi work with Desmond Child, a songwriter who’d been working with Kiss for a few years. Jon Bon Jovi was reluctant, but he went along with the plan and called Child up. (Child’s group Desmond Child & Rouge had peaked at #51 with the 1980 disco single “Our Love Is Insane.” Kiss’ highest-charting single, 1976’s “Beth,” peaked at #7. It’s a 4.)

Working with Bon Jovi and Sambora, Child basically plagiarized himself. In 1986, Child wrote “If You Were A Woman (And I Was A Man),” a Jim Steinman-produced synth-rock single for past Number Ones artist Bonnie Tyler. “If You Were A Woman” did OK in Europe, but it only made it to #77 on the Hot 100. Child thought the song deserved better. He brought it to Bon Jovi, keeping the same melody but rewriting the lyrics with Jon and Sambora.

Bon Jovi recorded “You Give Love A Bad Name” and the rest of their Slippery When Wet album in Vancouver with Bruce Fairbairn, a producer who’d gotten a big sound out of bands like Loverboy and Krokus. (Bon Jovi got the idea for the album’s title while watching a shower act at a strip club.) Like the rest of the LP, “You Give Love A Bad Name” sounds huge. The guitars sound like synths, and the synths also sound like synths. The drums boom. Sambora does Van Halen-style harmonic guitar screeches, though not with the same theatrical mastery. Jon Bon Jovi sings everything in an enthusiastic bray. There’s no subtlety in his vocal for “You Give Love A Bad Name,” but the song doesn’t call for subtlety. It’s a shout-along song, so he shouts it.

“You Give Love A Bad Name” jumps out of the speaker and refuses to be ignored. As my friend Chris Molanphy once pointed out on his great Hit Parade podcast, Bon Jovi start “You Give Love A Bad Name” with a gang-sung a cappella chorus — a trick that the boy bands of the late ’90s would later adapt. (Swedish factory-pop mastermind and future Bon Jovi collaborator Max Martin, a man who will eventually play a huge role in this column, spent the late ’80s leading the Swedish glam-metal band It’s Alive.) Right from those opening seconds, “You Give Love A Bad Name” has its blood pounding. It’s big and brash and silly, and it wants so badly to be loved.

“You Give Love A Bad Name” doesn’t rock in any way that ’80s metal bands like Twisted Sister or Ratt or Quiet Riot might recognize. There’s too much preening on the vocals, too much disco in the bass, too much synth in the everything. But those guitars crunch satisfyingly hard, and Bon Jovi mugs convincingly. The song has a boyish enthusiasm that translated into crossover gold. Even today, “You Give Love A Bad Name” is an impossible song to ignore. A couple of years ago, my eight-year-old son fell in love with “You Give Love A Bad Name.” His teachers would play the song during PE classes to get the kids fired up. It worked.

Lyrically, “You Give Love A Bad Name” is a romantically despondent freakout. Bon Jovi’s narrator is furious at some girl for playing games with his heart. She’s promised him heaven and put him through hell. His passion’s a prison, and he can’t break free. She’s a schoolboy’s dream, and she acts so shy, but her very first kiss was her first kiss goodbye. This is all textbook misogyny. Bon Jovi’s narrator can’t have this girl. He feels bad, and he blames her. But there’s no real acid to the song. Bon Jovi doesn’t sound anguished or angry. He sounds like he’s having a blast.

Bon Jovi were a band built, pretty explicitly, to appeal to women. This was a big part of why so many metal dudes hated Bon Jovi for so long. The bitterness in the “Bad Name” lyrics didn’t turn off that audience, and I think it’s because the song is too big and bouncy and good-natured. Bon Jovi clearly admires this girl with the ruby smile on her lips and the blood-red nails on her faaaaang-ertips. Who wouldn’t want to be that girl? The song is too silly to be mad. It’s a snarl with a wink. A whole lot of glam-metal bands would employ that same tactic, and plenty would have huge success with it.

In the context of the 1986 charts, “You Give Love A Bad Name” hits like an adrenaline needle. There’s no boomer synth-rock bluesiness to the song, no yuppie pandering, no smoothed-out adult-contempo gloop. Instead, much like Janet Jackson’s “When I Think Of You,” “You Give Love A Bad Name” is a game-changer — a sparkly and noisy new thing. Bon Jovi’s song would soon become even more consequential than Jackson’s. It would recalibrate pop radio’s ideas about what could and could not be played, which would lead to a massive influx of horny poodle-rock energy. Bon Jovi will appear in this column again, and their AquaNet brethren will arrive soon enough.

GRADE: 8/10