Those strings on the intro are an announcement, an almighty flex. Madonna’s

True Blue was her third album, but it was the first one she made when she was

already a massive star, a foundational pop-music figure. Up until then,

Madonna had been associated with a particular sound. Madonna made club music,

post-disco dance-pop. Even her ballads nodded to that sound. So it must’ve

been at least a little jarring for people to hear the fussy, rococo strings

that open “Papa Don’t Preach” — or, for that matter, to hear those strings

fade into a story-song about a pregnant teenager desperate for her father’s

approval. The strings nod to classical, to baroque, and to the Beatles-style

psychedelia that had made a big deal about incorporating strings like those a

couple of decades earlier. Madonna was doing what she felt like doing, and the

things she felt like doing were working.

“Papa Don’t Preach” wasn’t the first single from True Blue; that was “Live To Tell,” Madonna’s previous chart-topper. But “Live To Tell” was a movie-soundtrack ballad, and it came out months before the album. Masterful as it is, “Live To Tell” didn’t announce a great leap forward the way “Papa Don’t Preach” did. “Papa Don’t Preach” signaled that Madonna had enough juice to make a social-issue song that was also a stylistic left-turn. And for all its gutsiness, “Papa Don’t Preach” still worked as post-disco dance-pop. Its strings faded into jittery, propulsive synth-bass and big, mechanized drums, and this story about a girl begging her father to accept her big life decision somehow became escapist club fare. That’s a magic trick. That’s cowboy shit.

“Papa Don’t Preach” wasn’t supposed to be a Madonna song. A decade earlier, the songwriter Brian Elliot had tried to become a pop star himself, but his self-titled Warner Bros. debut hadn’t gone anywhere. By 1986, Elliot was producing demos for a singer named Christina Dent, who never really went anywhere either. Elliot had written “Papa Don’t Preach” for Dent, and he’d played the song for the Warner A&R executive Michael Ostin. Ostin liked “Papa Don’t Preach” enough to play it for Madonna, and she loved it. Ostin talked Elliot into giving “Papa Don’t Preach” to Madonna, and she turned the song into a whole other thing.

Madonna is credited as the co-writer of “Papa Don’t Preach,” but her contribution is apparently limited to a few added-on lyrics. And yet “Papa Don’t Preach” means more coming from Madonna than it would’ve meant from an artist who wasn’t yet established.

Part of it is the production. Madonna co-produced “Papa Don’t Preach” with her old friend and collaborator Stephen Bray, who she’d known since before dropping out of college. (Around the same time as he was working on True Blue, Bray joined a reconstituted version of the Breakfast Club, the band that Madonna had been in before she got famous, and they peaked at #7 with 1987’s “Right On Track.” It’s a 7.) But part of it is also the way “Papa Don’t Preach” plays into the persona that Madonna had already established.

On Like A Virgin, Madonna had weaponized her own sexuality, finding a transgressive lane within mainstream pop stardom and becoming a target of parents’ watchdog groups like the PMRC. But on “Papa Don’t Preach,” Madonna sang about a possible consequence of that sexuality. Her narrator is a teenager girl who is scared but determined. She’s not thrilled about the fact that she’s pregnant, but she’s made up her mind. She’s keeping her baby.

Naturally, “Papa Don’t Preach” became a political football. Anti-abortion groups claimed “Papa Don’t Preach” as an anti-abortion song. Tipper Gore, co-founder of the PMRC and pop-music boogeywoman, loved “Papa Don’t Preach,” calling it “an important song, and a good one, which discusses, with urgency, a real predicament which thousands of unwed teenagers face in our country.”

The feminist lawyer Gloria Allred, meanwhile, said that Madonna should “make a public statement noting that kids have other choices, including abortion.”

Madonna never made that statement. At the time, she didn’t say anything for or against abortion rights. The song never mentions the word “abortion.” When Madonna’s narrator sings that her friends are telling her to give the kid up, you don’t know if they’re talking about abortion or adoption. Maybe, for Allred, that was the problem. At the time, Allred said, “Pop songs have an enormous impact on kids today. They get their messages from music much more than from what they learn in school or in church. It becomes almost a religious message — a code or part of their belief system.” That’s pretty much what Tipper Gore had been saying, too.

It gets weird when people talk about pop music as messaging rather than as pop music. I do that shit all the time. Everyone in my line of work does. Maybe, if I’d been a professional critic in 1986, I would’ve had some kind of take on whether “Papa Don’t Preach” was an implied anti-abortion cop-out of a song. And maybe that’s how Brian Elliot meant it. (At the time, he said, “If Madonna has influenced young girls to keep their babies, I don’t think that’s such a bad deal.”) But “Papa Don’t Preach” isn’t a sweeping polemic about kids and sex. It’s a pop song — a great one.

For me, the strength of “Papa Don’t Preach” is in how limited and specific its scope is. Madonna’s narrator is one overwhelmed kid with a romantic idea in her head. It’s hard to imagine things turning out well for her and her boyfriend. You can hear the doubt in her voice when she’s imagining her own possible future: “He says that he’s going to marry me/ We can raise a little family/ Maybe we’ll be all right; it’s a sacrifice.” Her friends are telling her to go have a life instead, but she’s not listening. That stubbornness almost feels admirable, even if it means she’s going to have a hard future ahead of her.

I hear “Papa Don’t Preach” as being in the tradition of the girl-group songs of the early ’60s. (Elsewhere on True Blue, Madonna pays more direct tribute to that sound.) The best of those songs laid out storylines and situations. The point isn’t the resolution, and it certainly isn’t what that situation says about things happening in society. Instead, the point is the fear and love and anxiety and hurt that someone might feel in that moment. Madonna nails all of it.

“Papa Don’t Preach” is one more example of how Madonna, a technically limited singer, could always capture the feeling of the song. On the first verse, when she’s telling her father that she needs help, her voice is tremulous and hesitant. As the song goes on, her voice becomes stronger, but it keeps an anguish and a desperation. When she says that she and her boyfriend are in love, she sounds like she’s melting. When she pleads for her father’s blessing, she’s in agony. It’s a raw, messy conversation, and Madonna lets all those conflicting feelings bubble right up to the song’s surface. Her voice says more than the words do.

But those words say a lot, too. Madonna’s narrator contradicts herself; she says she needs some good advice immediately after talking about how she’s just ignored her friends’ good advice. She’s made up her mind to do something that may prove self-destructive. But the song never judges that narrator. The way Madonna delivers it, all you can feel is empathy.

For all the pathos of its story, though, “Papa Don’t Preach” still works as pop music. The beat is steady, but all the song’s flourishes — the strings, the quasi-Spanish guitar solo, the coos of the backup singers — float around that narrator, as if they’re consoling or encouraging her. (One of the backup singers, Siedah Garrett, will appear as a featured guest in a future column.) “Papa Don’t Preach” has hooks, too. It’s dainty and insistent and urgent, and it glues itself right into your brain the first time you hear it. If “Papa Don’t Preach” had been simply a message song, it would’ve aged like fine milk. But it’s not a message song. “Don’t Preach” is right there in the title. Instead, the song is a marvel of craft.

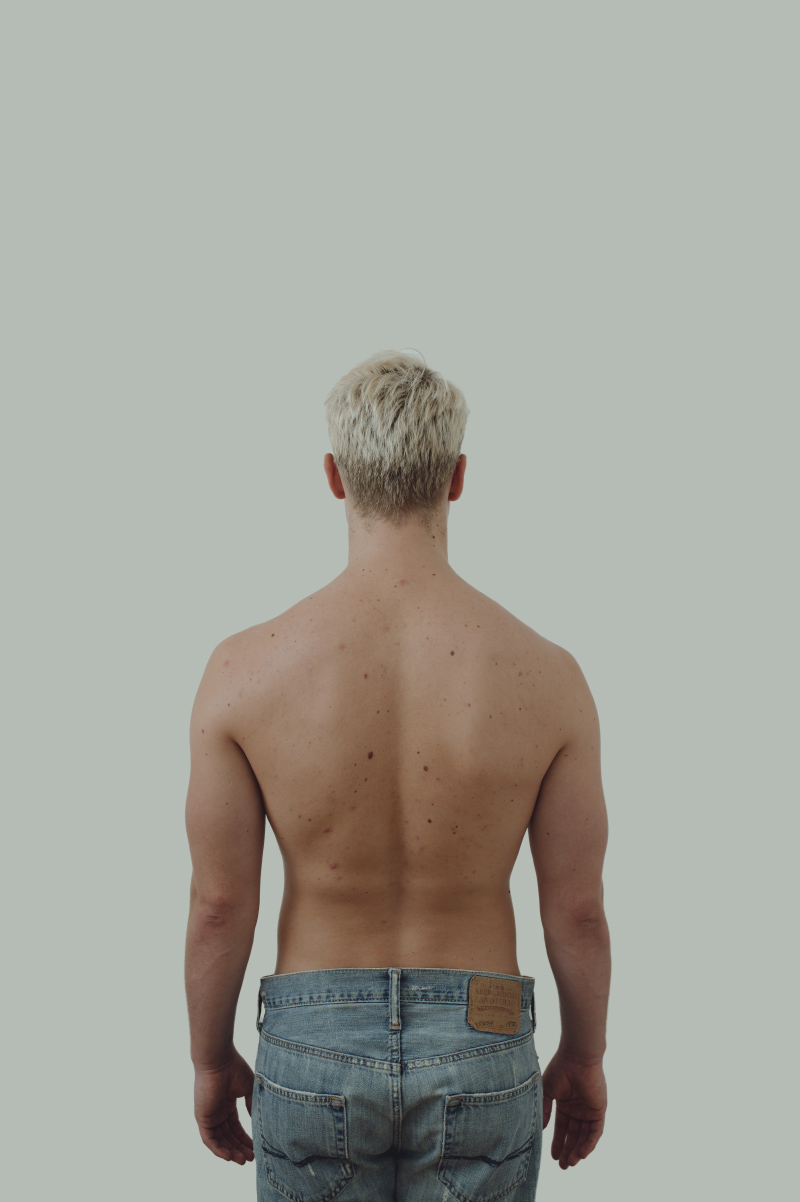

The video is pretty expertly crafted, too. Madonna made the “Papa Don’t Preach” video with director James Foley, the filmmaker who’d just directed her then-husband Sean Penn in At Close Range. Foley had directed Madonna’s “Live To Tell” video, but that one is really just Madonna close-ups and At Close Range clips. The “Papa Don’t Preach” video, on the other hand, is a whole mini-movie.

Madonna tries out a couple of different styles — the hyper-styled dancer of the performance clips and the tough tomboy of the narrative scenes. But the video is way more of a showcase for Madonna’s acting than for her ever-evolving persona.

Before rewatching it, I’d remembered “Papa Don’t Preach” as one those dialogue-heavy videos where you sometimes can’t hear the song because the director has decided to put words all over it. I was wrong. Instead, the “Papa Don’t Preach” clip plays out its whole storyline silently, and it does it so gracefully that you just imagine the dialogue scenes that don’t exist. Madonna plays a kid in Staten Island, one of the planet’s least glamorous places.

Danny Aiello plays her father, and both he and Madonna sell the resentment and the awkwardness and the ultimate reconciliation of the whole scenario. They’re both good actors, and they can get all this across without speaking.

At the time, Aiello was a character actor who mostly played cops and mobsters. He’d been in The Godfather Part II and Fort Apache, The Bronx and Once Upon A Time In America, but he hadn’t had especially meaty parts in any of them. The “Papa Don’t Preach” video probably helped make Aiello a whole lot more recognizable, and he had higher-profile roles in Moonstruck and Do The Right Thing just after “Papa Don’t Preach.” (Maybe Aiello should’ve given Madonna some pointers on picking scripts.)

The “Papa Don’t Preach” video also probably did good things for Alex McArthur, the extremely handsome young man who played the one Aiello warned Madonna all about. A year later, McArthur played a serial killer in William Friedkin’s Rampage. That was pretty much his entire run, though.

Watching the “Papa Don’t Preach” video today, it’s weird to think that Danny Aiello became way more of a star than Alex McArthur. McArthur has the kind of face that seems to demand Tiger Beat covers. Aiello does not. But Aiello could act, and he had personality. Sometimes, those things matter.

The “Papa Don’t Preach” video is made with style and grace, but it’s the song that really does the heavy lifting. “Papa Don’t Preach” rules, but it isn’t one of my favorite Madonna songs. There’s an intensity to her best tracks that I don’t really hear in “Papa Don’t Preach.” Maybe there’s just a bit of distance because I know she’s singing in character, or maybe I just prefer my dance-pop catharsis raw and uncut. But “Papa Don’t Preach” is still a masterful piece of pop craftsmanship — one more great entry in an all-time run. We will see Madonna in this column again.

GRADE: 9/10