According to one of our preferred sources:

When the World’s Fair came to Queens in 1964, the shiny, chromed-out architecture on display was supposed to represent the dawn of the Space Age — a new global era when humanity was reaching beyond what was possible and jumping optimistically into the future. Those buildings soon became part of New York’s kitschy iconography, but kitsch has its own power, too. In the summer of 1997, those World’s Fair constructions, still standing in Flushing Meadows, appeared in two of the the summer’s great escapist entertainment spectacles.

There was, for instance, Men In Black, the blockbuster that turned once-and-future rapper Will Smith into the biggest movie star in the world. (Will Smith will appear in this column pretty soon.) At the end of the film, we learn that the elevated discs of the New York State Pavilion are really disguised flying saucers, and a bug-monster guy tries to use them to escape Earth. He doesn’t succeed.

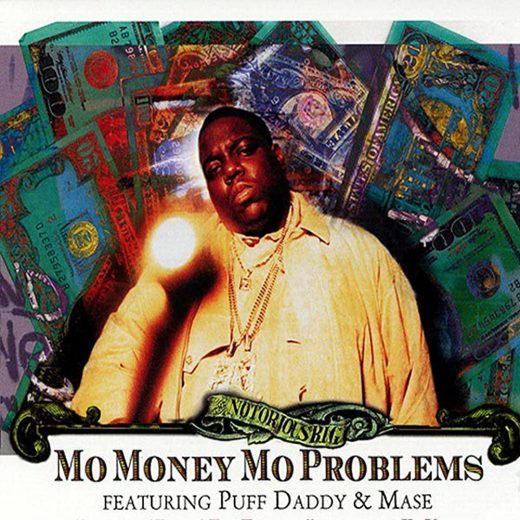

Two weeks after Men In Black arrived in theaters, Bad Boy Records released “Mo Money Mo Problems,” the second posthumous single from the late Notorious B.I.G. Hype Williams’ video for that song — a piece of filmmaking as sleek and iconic, in its own way, as Men In Black — takes place partly in the shadow of the Unisphere, the 140-foot stainless steel globe that Gilmore D. Clark designed to promote the idea of worldwide peace through understanding. In the context of “Mo Money Mo Problems,” that globe represents something else. It makes a nice visual representation of Bad Boy’s year of all-conquering chart dominance — the biggest sustained run of Hot 100 success since the Bee Gees in 1978. The Unisphere glimmers in the background while Puff Daddy and Mase, all decked out in their era-defining shiny suits, dance the night away.

“Mo Money Mo Problems” was Biggie Smalls’ second #1 hit. Both that song and “Hypnotize,” Biggie’s previous chart-topper, reached #1 after Biggie’s murder. In between those two chart-toppers, Biggie’s label boss Puff Daddy held down the #1 spot for 11 long weeks with his Biggie tribute “I’ll Be Missing You.” That year, Bad Boy’s iron grip on the pop charts was both terrifying and awe-inspiring, and most of its hits were directly catalyzed by Biggie’s death. Biggie was only alive for two months in 1997, but he towered over the entire pop-music landscape for the entire year. In the entire history of the Hot 100, only a few artists have topped the chart posthumously. Biggie is the only artist in history who’s done it more than once. It’s a true mark of a titan: This guy was still making hits months after his body was cremated.

You could argue that the success of “I’ll Be Missing You” reflected people’s sadness and shock over Biggie’s murder, though the song had lots of other stuff going on, too. “I’ll Be Missing You” reached #1 in countries where Biggie himself was barely known, so that song hit some kind of cultural chord that went beyond Biggie, but it’s still a song about the loss of Biggie. Biggie’s two chart-toppers, by contrast, aren’t even remotely sad. They’re both triumphant party jams, songs for celebrating, and that’s how they were received.

“Mo Money Mo Problems” is on Biggie’s Life After Death album, and Biggie is the credited lead artist and the best thing about the song. But “Mo Money Mo Problems” isn’t really Biggie’s track. Instead, it’s a pure example of the Puff Daddy approach to hitmaking. Biggie’s voice doesn’t appear until the song is past the two-minute mark, and its whole flashy sugar-rush vibe is pure Puff. As with so many other Bad Boy hits from that era, “Mo Money” is built from a huge chunk of a song that was already massive. In this case, the song in question is Diana Ross’ 1980 disco anthem “I’m Coming Out.”

“I’m Coming Out,” comes from Diana, the album that Diana Ross recorded with Chic auteurs Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards — the same LP that gave us Ross’ perfect chart-topper “Upside Down.” At the time, Rodgers and Edwards were only just starting to write and produce songs for artists from outside their camp, and “I’m Coming Out” could’ve easily been a Chic or Sister Sledge track. For obvious reasons, the song became a gay-club anthem almost immediately. This was intentional.

Decades after its release, Nile Rodgers confirmed that he wrote “I’m Coming Out” specifically with the gay community in mind. Rodgers had been to a New York drag club, and he’d noticed that multiple drag queens had made themselves up to look like Ross. Rodgers told the story just last year in a TikTok video: “Diana Ross is revered by the gay community. If we wrote a song called ‘I’m Coming Out’ for Diana Ross, it would have the same power as James Brown’s ‘Say It Loud – I’m Black And I’m Proud.’”

Diana Ross loved “I’m Coming Out,” and she interpreted the song as her own statement of personal liberation. She’d left Motown and Berry Gordy behind, and she’d become her own artist. She didn’t know what “coming out” meant in a gay context. In a BBC documentary a couple of years ago, there was a story about Ross finding out that phrase’s meaning from the radio DJ Frankie Crocker. Apparently, Ross got extremely upset, and she demanded to know why Rodgers and Edwards were trying to ruin her career.

“I’m Coming Out” did not ruin Diana Ross’ career. It’s a euphoric liquid dance track with a nasty Chic groove and, weirdly enough, a trombone solo from former Number Ones artist Meco. Presumably, like so many Village People songs, “I’m Coming Out” still sounded great to people who had no idea what the lyrics meant, and the song peaked at #5. (It’s a 9.) Puff Daddy co-produced “Mo Money Mo Problems” with regular collaborator Stevie J. Never shy about lifting huge pieces of the songs that he sampled, Puffy looped up the “I’m Coming Out” groove. Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards got co-writer credits, so “Mo Money Mo Problems” was also a posthumous hit for Edwards, who’d died suddenly of pneumonia after a Chic show in Japan a year earlier.

Puff brought in the great soul and gospel wailer Kelly Price to sing a reworded version of the “I’m Coming Out” hook on “Mo Money Mo Problems.” (Kelly Price has come up in this column before because she sang backup on Mariah Carey’s “Always Be My Baby.” Price’s highest-charting lead-artist single, the R. Kelly/Ronald Isley collab “Friend Of Mine (Remix),” peaked at #12. Price was also a featured guest on Whitney Houston’s “Heartbreak Hotel,” which peaked at #2. It’s an 8.) For whatever reason, Kelly Price doesn’t get a featured-artist credit on “Mo Money Mo Problems,” even though you can hear hear ad-libs all over the track.

The lyrical changes on the “Mo Money Mo Problems” hook make a difference. However you read it, “I’m Coming Out” is a song about personal liberation. “Mo Money Mo Problems,” at least on paper, is a song about all the headaches that can come from success: “I don’t know what they want from me/ It’s like the more money we come across, the more problems we see.” But then, “Mo Money Mo Problems” isn’t really about problems. Unless you count the looming and unspoken absence of Biggie himself — not a “problem” so much as an actual real-life tragedy — “Mo Money Mo Problems” barely bothers to identify any problems at all. Instead, it’s a dizzy victory lap, all sly arrogance and bad-winner taunting. Maybe “Mo Money Mo Problems” is still a song about personal liberation — the kind of freedom that you can only feel if you’re very, very paid.

Most big Bad Boy singles worked as showcases for multiple Bad Boy artists, and “Mo Money Mo Problems” is no exception. The song’s leadoff verse belongs to Mase, who was fresh off of his turn on Puffy’s first chart-topper “Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down” and who released the debut album Harlem World a couple of months after “Mo Money” reached #1. Like Puffy himself, Mase mixed over-the-top bravado with sleepy, monotonal delivery, and it took me way too long to figure out that Mase does that style much, much better than Puffy ever could. Mase’s opening verse is loose and silly, but he stays in the song’s pocket and gets off some nice lines. He knows his duty — stay humble, stay low, blow like Hootie — and he spends no dough on the booty. (Hootie & The Blowfish’s highest-charting single, 1995’s “I Only Wanna Be With You,” peaked at #6. It’s a 5.)

Puff Daddy’s own “Mo Money Mo Problems” verse is better than some of the other Puff verses from that stretch of time, though not by much. I always liked the line about being bigger than the city lights down in Times Square, yeah yeah yeah. But Puffy still sleepwalks through the song, emphasizing nothing and finding no interesting flows. In the moment — the stretch of months when the only non-Bad Boy song to reach #1 was “MMMBop” — Puffy’s dominance seemed shattering, apocalyptic. This guy who couldn’t rap had broken the pop-rap formula wide open, and his presence felt oppressive. Decades later, when I don’t have to worry about hearing Puffy groggily muttering every time I turn on the radio, he still sounds pretty bad. The best thing I can say about circa-’97 Puffy as a rapper is that the man was confident. He really felt like he could share Biggie’s mic.

He couldn’t. He did, but he couldn’t. When Biggie Smalls touches down on “Mo Money Mo Problems,” the song’s whole chemistry immediately shifts. It happens before Biggie even raps, when his fired-up grunt finds the song’s pocket. (I’m a big fan of starting a rap verse with a couple of seconds of “unh,” and Jay-Z is the only person who ever did that as well as Biggie.) Biggie’s opening line is an all-timer: “B-I-G! P-O! P-P-A! No info! For the! DEA! Federal agents mad ’cause I’m flagrant! Tapped my cell and the phone in the basement!” In the song’s logic, feds are the biggest problem that comes with money, but Biggie doesn’t sound bothered.

Biggie was always reluctant to wholeheartedly embrace Puff Daddy’s whole explosive pop-rap aesthetic, but on “Mo Money Mo Problems,” he commits completely. There is so much pure, joyous exuberance on Biggie’s verse, even when he’s talking about dangerous situations. He makes “gats in holsters, girls on shoulders” into a perfect party line, even though I would never put a girl on my shoulders if she had a gat in a holster. (It just seems like it would be inviting some kind of horrible accidental slapstick injury.)

Biggie taunts, too: “Step onstage, the girls boo too much! I guess it’s ’cause you run with lame dudes too much!” But even as he plays those power games, Biggie’s voice is just so welcoming. When he asks you to throw your Rolies in the sky, it’s an automatic signal to put your hands up, whether or not you actually own a Rolex. (A lot of people heard that line as “throw your roadies in the sky,” even though Puff and Mase helpfully demonstrate with their own Rolies in the video. That’s a funny image, but that’s not what Biggie’s saying to do. Leave your roadies on the ground.)

“Mo Money Mo Problems” is, at the very least, a pretty good rap song with one great verse. But the song doesn’t give me the instant endorphin rush that it seems to cause in so many others, and I have a particular personal reason for this. The summer of 1997 was my second year working as a counselor at a residential camp in western Maryland, deep in the woods. One of my co-workers was this kid named Lucky who always walked around with a boom-box and who only ever listened to “Mo Money Mo Problems.” I wish I ever loved anything as much as Lucky loved that song. That’s the only track I ever heard coming out of Lucky’s radio, and I got so sick of it. That’s my problem, not a problem for “Mo Money Mo Problems.” But music criticism is a subjective thing, and Lucky pretty much ruined “Mo Money Mo Problems” for me.

Puff Daddy and Hype Williams were faced with the unenviable task of making a video for an artist who wasn’t around to appear in it. For Puff Daddy, that was never a problem; he simply made the video about himself. Biggie appears in the “Mo Money Mo Problems” clip via archival footage — live-show video synced up to look like he’s doing the song, home footage of Biggie talking about money and problems while being filmed from an extremely unflattering angle. Most of the video is just Puff Daddy doing Puff Daddy things — winning a golf tournament, for instance, and then crediting Biggie’s spirit as his inspiration. This seemed terribly self-serving at the time, but now it’s at least a little bit charming that this guy restaged Tiger Woods’ early career, making it look like a Rodney Dangerfield comedy from the ’80s.

Today, the “Mo Money Mo Problems” video stands as the purest version of peak-era Bad Boy spectacle. When people talk about rap’s Shiny Suit Era — and if you spend enough time talking about rap, it comes up again and again — they are referring to Puff and Mase’s wardrobe choices in this video. Here’s Puff and Mase walking away from a slow-motion explosion. There’s Puff and Mase in zero-gravity, too fly to remain earthbound. Here’s Puff and Mase dancing together in front of the Unisphere, or dancing together in a room full of artfully designed fluorescent lights, playing directly to Hype Williams’ fisheye lens. Those guys just loved dancing together. They were good at it, and it’s fun to watch them go. The whole thing is pure motion, with Mase’s smile shining in every direction. In the face of real death, they looked utterly undefeated. In retrospect, this was the point.

Biggie didn’t have a third posthumous #1 hit in him. The third single from Life After Death was the smoothed-out 112 collaboration “Sky’s The Limit,” which peaked at #26. The song itself was nothing special, but I’ve always loved the Spike Jonze video, where little-kid doppelgangers play Biggie, Puffy, and their various associates.

Unlike Tupac Shakur, Biggie didn’t leave behind a vast trove of unreleased material when he died. Bad Boy still assembled a couple of posthumous Biggie albums, building tracks from Biggie’s unfinished verses. The 1999 album Born Again went double platinum, and its lead single, the Duran Duran-sampling Puffy/Lil Kim collab “Notorious B.I.G.,” peaked at #82. In 2004, the stitched-together Eminem-produced Tupac/Biggie collab “Runnin’ (Dying To Live)” made it as high as #19. Really, though, Biggie didn’t need more posthumous hits to maintain his status as one of the all-time rap greats. He solidified that status with the music that he actually recorded while he was alive.

Mase went quadruple platinum with Harlem World, and the album yielded three top-10 hits. (The biggest of them, the Kelly Price collab “Feel So Good,” peaked at #5. It’s an 8.) But before Mase released his 1999 sophomore album Double Up, he announced that he’d been called by God to retire from rap. Mase started studying at Clark Atlanta University, and he became a minister. A few years later, Mase returned, releasing the 2004 album Welcome Back and briefly signing with 50 Cent’s G-Unit label. (50, who will eventually appear in this column, definitely learned a lot from Mase’s delivery.) Mase seems to reappear every few years, rapping a guest-verse or popping up on a Bad Boy reunion tour, but he stopped being an active chart presence the moment that he announced that short-lived retirement.

Puff Daddy, meanwhile, did not stop. We will see him in this column again very soon.

GRADE: 7/10 – The Number Ones: The Notorious B.I.G.’s “Mo Money Mo Problems” (Feat. Puff Daddy & Mase) (stereogum.com)