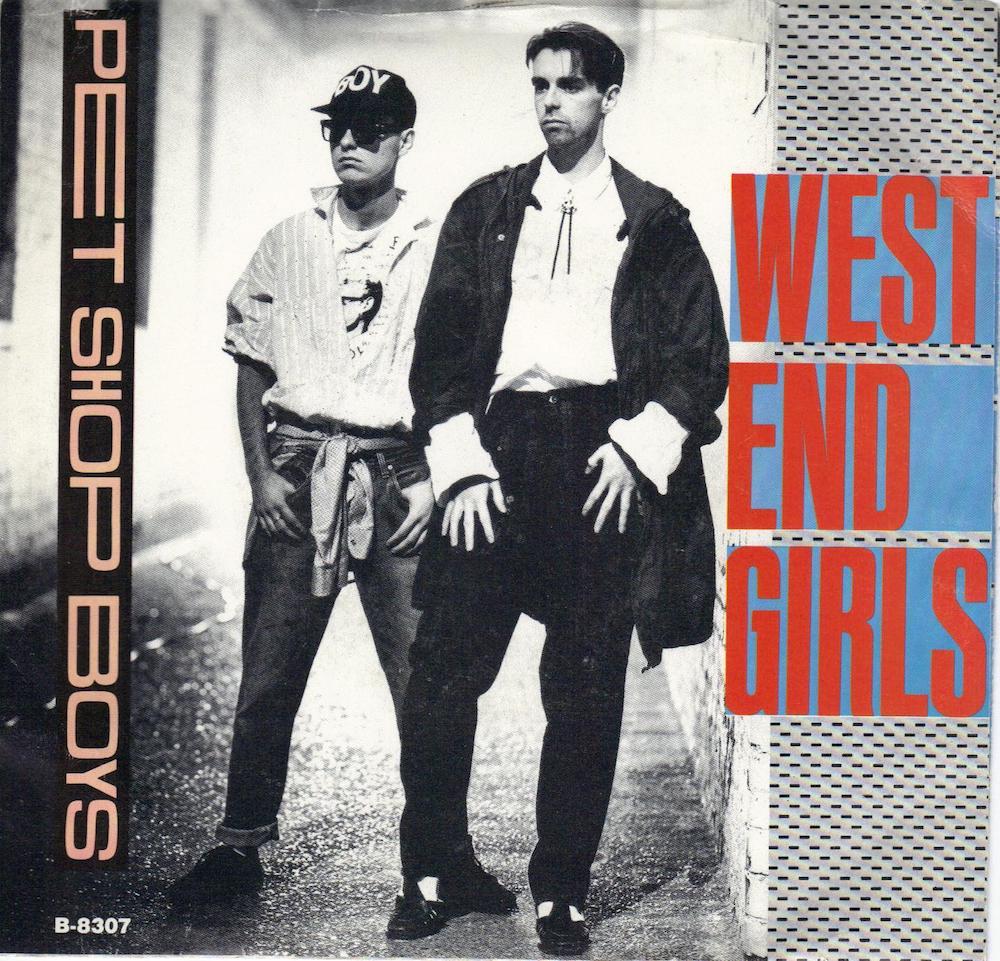

According to one of our musical sources:

“There’s a phrase that I’ve used in this column enough times that I’ve

probably worn it out: The imperial phase. That’s the point of a career where a

musician is in an absolute zone, where she’s at the zenith of her popularity,

where everything she does makes sense to the public. An artist in the imperial

phase can do anything, and a vast audience will happily accept it. The man

that coined that phrase and codified that concept is Neil Tennant, the

slightly more animated of the two Pet Shop Boys. When Tennant came up with

that term, he was talking about his group’s late-’80s run, where all their

singles soared up near the top of the UK charts. In the US, the Pet Shop Boys

didn’t exactly have an imperial phase, but they did have a run, and they did

score one glorious and unlikely #1 single.

Tennant was uniquely qualified to assess his own career and to come up with

pithy ideas to describe it. Before he found pop stardom, Tennant was a pop

critic, an editor at the UK magazine Smash Hits. That means that Tennant is my people. Unless I’m forgetting something,

Tennant is the only critic ever to score a #1 hit. One of the most magical

things about the Pet Shop Boys’ whole run is that it’s recognizably music made

by a critic. As a vocalist, Tennant has always been aloof and detached, as if

he’s commenting on the things he’s depicting in his songs rather than living

those things. Being permanently stuck inside your own head is a quality that

many people of my profession share. But Tennant is also clearly a lover and a

connoisseur of pop music — someone who thinks and feels long and hard about

the sounds he’s hearing in the world, who processes those sounds and

translates them into something else.

You could almost imagine the Pet Shop Boys’ best records as acts of pop

criticism. Tennant stripped away all the stuff from pop music that he thought

was stupid: The guitar-shredding, the blues-descended howling, the constant

striving for someone’s idea of authenticity. He’s never much cared for rock

‘n’ roll or any of its stylistic descendants. Instead, Tennant and his Pet

Shop Boys partner Chris Lowe have long found inspiration in different waves of

underground dance music: Disco, hi-NRG, rap, house, Latin freestyle. As a gay

man who lived a nightclub life, Tennant experienced those sounds and shaped

them into a whole approach.

“West End Girls,” the Pet Shop Boys’ only Hot 100 #1, is that approach in

action. The song couldn’t exist without Tennant’s pop-critic background, his

love of underground sounds, or his deadpan outsider perspective. With the

song, he and Lowe almost accidentally hit upon a sound that, against odds,

resonated as pop music on a global level. That’s some kind of miracle.

Tennant came from a small coastal English town and grew up subjected to the

strict religious upbringing that would later inspire the Pet Shop Boys’

classic 1987 conflicted-Catholicism smash “It’s A Sin.” (“It’s A Sin” peaked at #9. It’s a 10.) As a teenager, Tennant played in a

folk band called Dust. Then, after college, he moved to London and found work

as an editor at the UK office of Marvel Comics, where he was tasked with

making the dialog more British. From there, Tennant became a book editor and

then found his way to Smash Hits.

In 1981, the same time that he started at the magazine, a 27-year-old Tennant

met 21-year-old Chris Lowe at a hi-fi shop. Tennant was having the wires of

his keyboard welded to his sound system, and Lowe struck up a conversation

about synths. Soon after, Lowe came to Tennant’s house to check out that

keyboard, and they started writing songs together.

For a few years, the Pet Shop Boys weren’t really a band; they were more of a

theoretical proposition. Tennant and Lowe would put song ideas to tape, but

they weren’t out performing. In 1983, Smash Hits sent Tennant to New York to interview the Police, a group whose music

he didn’t much like. (I wish people would send me across the Atlantic to

interview people who live in the same city as me, but that era seems to be

over.) While Tennant was in New York, he tracked down Bobby Orlando, a

producer who made underground hi-NRG dance jams that Tennant and Lowe both

loved.

Bobby Orlando’s tracks weren’t exactly trans-Atlantic hits, and he was happy

to meet a British writer who was excited about his music. Orlando agreed to

produce the Pet Shop Boys, and so Tennant and Lowe returned to New York

shortly thereafter to record some songs with Lowe. One of those songs was

“West End Girls,” an impressionistic free-floating account of urban London

glamor and squalor. Tennant’s East End boys are the brutish young men of

working-class London; his West End girls are the monied young women attracted

to those boys.

There’s no real narrative to “West End Girls.” Instead, Tennant muses about

class and attraction, about the threat of violence that lies under the surface

of those interactions. He flips the Sex Pistols’ line about “no future for

you”: “We’ve got no future, we’ve got no past/ Here today, built to last.”

Tennant also alludes to the way that class conflict reappears throughout

history, mentioning Vladimir Lenin’s return to Russia from Germany: “In every

city, in every nation/ From Lake Geneva to the Finland Station.” (The original

version of the song also rhymed “all your stalling” with “who do you think you

are, Joe Stalin?”)

“West End Girls” opens with Tennant zoning out on an image of desperation:

“Sometimes, you’re better off dead/ There’s a gun in your hand, and it’s

pointed at your head.” Tennant has said that he was inspired by both TS

Eliot’s 1922 modernist poem The Waste Land and by Grandmaster Flash And The Furious Five’s 1982 urban-hunger rap

classic “The Message.” (“The Message” peaked at #62. It’ll eventually appear,

in sampled form, in this column.)

Tennant has said that he was trying to write a rap song with an English

accent. That’s not what “West End Girls” is. Tennant may have loved rap music,

but he wasn’t rapping any more than fellow 1986 chart-topper Falco was on “Rock Me Amadeus.” Instead, Tennant’s detached vocal has a lot more to do with the reserved,

icy sing-speak of early-’80s UK synthpoppers like Soft Cell’s Marc Almond or

the Normal’s Daniel Miller.

When Tennant and Lowe recorded “West End Girls” with Bobby Orlando, Orlando

programmed in the drums from Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean.” He recorded the duo live-to-tape, then overdubbed a bunch of the synth

effects that he used on his hi-NRG records. There’s a bright, appealing

crudeness to the Orlando version of “West End Girls,” which Orlando released

on his label O Records.

At that point, Tennant and Lowe thought of “West End Girls” as a New York

dance record. Earlier this year, Tennant told The Guardian, “At this point, our career ambition was to have a record you could only buy

on import in the gay record shop on Berwick Street, which we used to hang

around in and where I used to buy imports on my Smash Hits expenses. And we achieved that — by September 1984, you could only buy

‘West End Girls’ on a Canadian import in the Record Shack. Even as I say that

to you, I’m quite thrilled.”

“West End Girls” did well in the dance clubs of a few American cities, and

then it randomly took off in France and Belgium, making the charts in both

countries. Tennant and Lowe found a manager, who got them a deal at EMI. This

meant that they had to sever ties with Bobby Orlando, which resulted in a

legal battle and prevented them from making any new records for more than a

year. The duo didn’t get the rights to release the Orlando version of “West

End Girls,” so they re-recorded all the tracks they’d recorded with Orlando

with producer Stephen Hague, an American who’d worked with British new wavers

like Malcolm McLaren (a fellow pseudo-rapper) and Orchestral Manoeuvres In The

Dark.

The Stephen Hague version of “West End Girls” is the one we know. Hague made

the song sleeker and more layered. He added sound effects, transforming it

into something more cinematic. (Like “The Message” before it, “West End Girls”

has the sound of breaking glass.) Hague’s drums sound less like “Billie Jean,”

and he adds in foggy hums and lonely trumpets and echo-drenched backup vocals

from session singer Helena Springs. That Hague version of the song came out in

late 1985, a year and a half after the original O Records version of the song.

In its final form, “West End Girls” is a rich, layered pop song that still

keeps some of its strange, stilted otherness of the original. Neil Tennant

doesn’t really rap, but he doesn’t really sing, either. Instead, he comes off

like a narrator, dispassionately describing scenes of passion, sounding both

amused and bemused. It’s got a sense of mystery to it, and the video only

enhances that. In the clip, from Wham! director Andy Morahan and Smash Hits photographer Eric Watson, Tennant and Lowe wander, blank-faced, through

London, never looking surprised or excited. Much of the time, Lowe is

half-transparent, like a ghost.

“West End Girls” is a great song, but it doesn’t sound, at least to my 2020

ears like a hit — or, at the very least, a centrist American pop-radio hit. Instead,

it’s something that came from the margins to conquer the center, and I always

love stories like that. Partly by sounding like nothing else at the time,

“West End Girls” became a true global smash, a #1 record in the US, the UK,

Canada, Israel, New Zealand, Hong Kong. Maybe there really are East End boys

and West End girls in every city, in every nation.

“West End Girls” could’ve easily been a novelty. It wasn’t. In the US, the Pet

Shop Boys had four more top-10 hits. Please, the duo’s debut album, went platinum, and one more of its tracks, an

electro remix of the deeply sardonic “Opportunities (Let’s Make Lots Of Money),” reached #10. (It’s an 8.) A year later, the duo teamed up with the

blue-eyed soul goddess Dusty Springfield, who’d been missing from the charts

for years, and they made it up to #2 with the duet “What Have I Done To

Deserve This?” (That song, which remains Springfield’s highest-charting US

single, is a 10.)

In the US, the Pet Shop Boys made the top 10 for the last time in 1987,

when their cover of the country classic “Always On My Mind,” previously a hit for both

Elvis Presley and Willie Nelson, peaked at #4. (The Pet Shop Boys’ version is

another 10.) But at home in the UK, the Pet Shop Boys became a beloved

national-treasure pop institution. They racked up dozens of top-10 hits;

through the end of the ’90s, barely any of their singles missed the top 20. At

this point, it’s probably not a stretch to say that the Pet Shop Boys are a

part of British cultural identity. In 2012, for instance, they performed a

strange and elaborate version of “West End Girls” at the closing ceremony of

the London Olympics.

But maybe it’s more accurate to say that the Pet Shop Boys, the group that

figured out how to turn criticism into pop, are part of our global pop

heritage. In 2015, for instance, the Pet Shop Boys were given the Worldwide

Inspiration Award at the MAMA Awards in Hong Kong — a K-pop-centric

spectacular that also featured future Number Ones subject BTS. Tennant sang

that night with the Korean girl group f(x), and the Pet Shop Boys were the

only Western group to perform.

The Pet Shop Boys remain active. Earlier this year, they released a new album.

This summer, they were supposed to tour with fellow dance-pop survivors New

Order, but the pandemic ended those plans. Instead, the Pet Shop Boys gave a

remote performance of “West End Girls” at the Smithsonian Pride festival in

June. They’re still figuring out new things to do with the song, and the song

still kicks.

Another thing happened with “West End Girls” in June. The Guardian named it the greatest British #1 single of all time. I don’t agree

with The Guardian. For my money, the Pet Shop Boys truly became great on their 1987 sophomore

album Actually, when they sweetened their sound up with thicker beats and prettier

melodies. “West End Girls” slaps, but it’s not the best of the duo’s British

chart-toppers, let alone of the entire history of the UK pop charts. I

like The Guardian‘s pick, though. You could do a lot worse.

To mark the occasion, Tennant did a Guardian interview with my friend Laura Snapes. In that conversation, he tells all sorts

of great stories about making “West End Girls,” about the song’s rise to smash

status. By the end of it, though, Tennant and Snapes are just bullshitting

with each other about other great #1 hits, and about songs that should’ve

topped the charts but didn’t. I’m telling you: Neil Tennant is my people. If

you’re reading this, he’s your people, too.

GRADE: 9/10

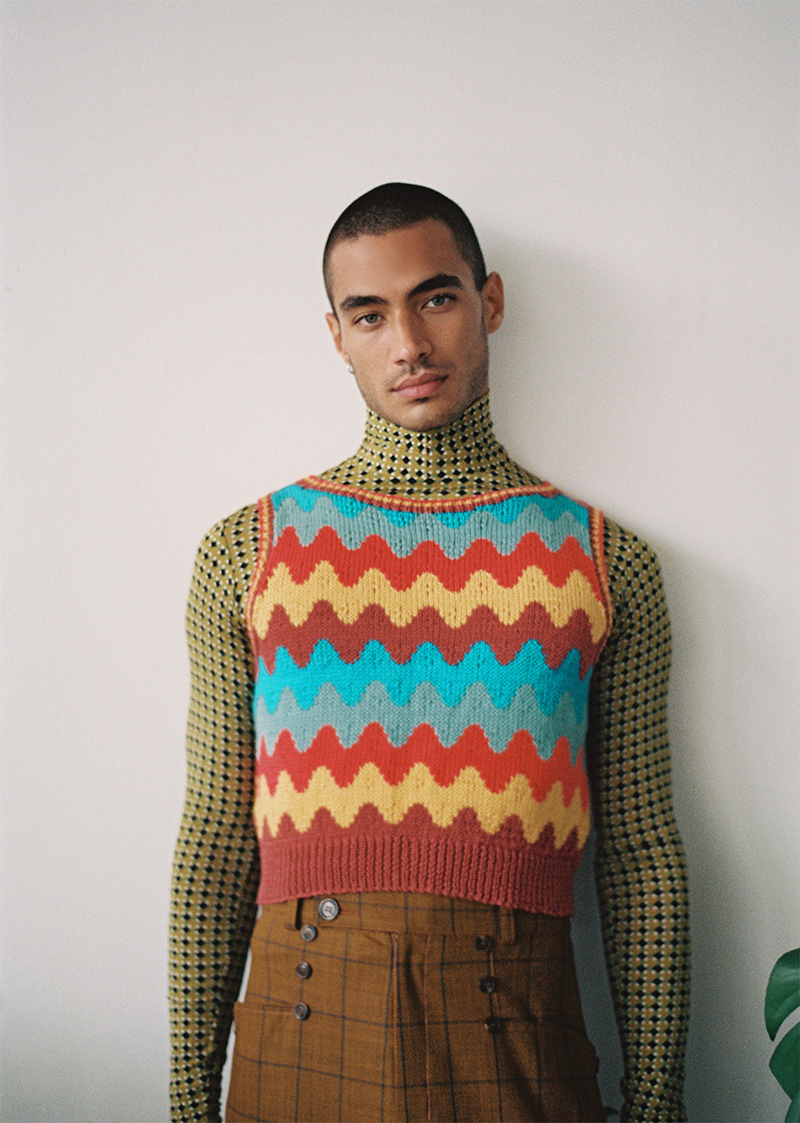

BONUS BEATS: In 1993, the British boy band East 17 had a hit across Europe and

Oceania with a deeply unnecessary cover of “West End Girls.” Here’s their very

silly video, which features at least three different outfits that I wish I

owned:

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here’s the goofy lark of a “West End Girls” cover that My Morning

Jacket included on a 2004 early-recordings compilation:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here’s Flight Of The Conchords’ 2008 “West End Girls” parody “Inner

City Life”:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here’s noise-rap experimentalists Death Grips playing around with a

“West End Girls” sample on “5D,” a short instrumental interlude from the 2011

mixtape Exmilitary:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here’s the pretty-great 2014 episode of the AV Club’s AV Undercover video series where the beloved Virginia institution Gwar bash out a

pretty fucking badass “West End Girls” cover, then careen headlong into a

version of the Jim Carroll Band’s “People Who Died” that salutes fallen

frontman Dave Brockie:

THE 10S: Phil Collins’ dazzling, heartsick bleeps-like-raindrops odyssey “Take

Me Home” peaked at #7 behind “West End Girls.” It helps to keep me warm, and

it’s a 10.