According to one of our musical sources…

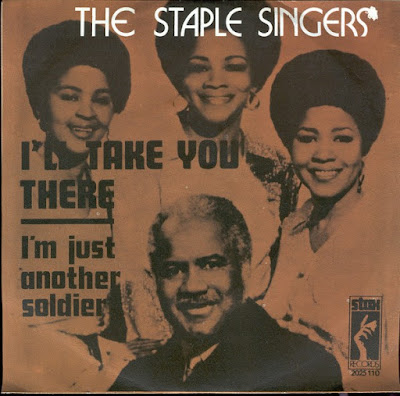

The Staple Singers – “I’ll Take You There”

HIT #1: June 3, 1972

STAYED AT #1: 1 week

Does a religious song have to be about a specific system of beliefs? Does it have to invoke deities, or denominations, or holy words? Or can it just be a song about imagining a better place, a better future?

The Staple Singers’ “I’ll Take You There” never mentions any particular god, or any set of beliefs. It only imagines a place where things are better. But it’s still hard to hear it as anything other than a gospel song — one of the purest and most direct that ever went to #1 in America.

Like Sam Cooke and Aretha Franklin and Al Green, the Staple Singers came from gospel. And they also kept using gospel to inform their pop music. But the Staple Singers’ transition to pop music wasn’t as simple and immediate as those other stars’. It was more of a gradual thing. Gospel became message music, which became soul music, which became some form of pop music. Even when the Staple Singers were singing about sex, they were doing it as a family gospel band. And while there were certainly people within the gospel establishment who rejected what they were doing, the family kept those ties strong.

The Staple Singers were the creation of Roebuck “Pops” Staples. Pops, born in 1914, was the youngest of 14 children, and he grew up on a cotton plantation in Mississippi. Pops dropped out of school in eighth grade, and as a young man, he played with blues musicians like Charlie Patton and Robert Johnson. At 21, he moved his family to Chicago, where he worked in stockyards and steel mills. In 1948, the Staple Singers — Pops, his wife Oceola, and three of their four kids — began singing at Chicago’s Mount Zion Church, where Pops’ brother Chester was pastor. Mavis, the youngest of them, was about 11.

The Staple Singers started recording in 1952, for a bunch of different labels. In the beginning, they were making straight-up gospel music, and they captured a lot of people’s imaginations. The Rolling Stones adapted their 1955 song “This May Be The Last Time,” transforming it into their 1965 song “The Last Time.” (“The Last Time” peaked at #9. It’s a 10.) Bob Dylan later wrote about being fascinated with their 1956 take on the gospel traditional “Uncloudy Day,” on which the young Mavis sang lead. By 1965, the Staple Singers had moved to Epic Records, where they recorded Freedom Highway, an album explicitly inspired by the Civil Rights struggle. From there, they started covering popular songs like the Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth,” blurring the line between gospel music and secular pop. And in 1968, they signed to Stax.

Al Bell, the vice president and co-owner of Stax, signed the Staple Singers, and he’s also the sole credited writer of “I’ll Take You There,” the Staple Singers’ first #1 hit. Bell tells a story about how he wrote “I’ll Take You There” in a mental fog. His younger brother had been murdered in Little Rock, and he was in his father’s backyard just after the funeral when the words of the song came to him. He says he tried to think of more words, to flesh the song out, but they just wouldn’t come, so he let the song be what it was. Mavis Staples tells a different story. She says that she and Bell co-wrote the lyrics on the living-room floor of her Chicago apartment. Mavis was, and is, furious about not getting a co-writing credit; it’s part of the reason the Staple Singers left Stax in 1975.

In any case, Al Bell didn’t write all of “I’ll Take You There.” The song’s intro came from “The Liquidator,” a 1969 reggae instrumental from Harry J Allstars. (Some of the musicians who played on the song later joined Bob Marley’s Wailers and Lee Perry’s Upsetters.) Bell had bought “The Liquidator” in Jamaica. When he produced “I’ll Take You There,” he played “The Liquidator” for the musicians in the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, one of the all-time great studio bands. The Muscle Shoals guys claim that they didn’t know “The Liquidator” was someone else’s record. According to them, they thought they were just playing the parts from Bell’s demo or something. But a few of the Muscle Shoals guys were just getting into reggae, and they figured out how to transform that titanic bassline into sweaty, funky Southern soul. Reggae had already started making inroads into the US, and Desmond Dekker’s 1969 single “Israelites” had made it up to #9. (It’s a 10.) But “I’ll Take You There” might be the first reggae-influenced single to make it to #1 in America.

“I’ll Take You There” is one of the bright, shining examples of the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section at work. The song itself is a simple call-and-response — no verses, no choruses — so the band gets plenty of room to groove. And they are so tight, so locked-in, while at the same time so breezy and unfocused, giving each other space to run around and wander. Bassist David Hood eventually eases out of that bassline; I love the bit where he lets a whole new bassline into the song. Keyboardist Barry Beckett floats over everything, unbothered and unhurried. There’s a part where the guitar solo kicks in and Mavis Staples sings, “Daddy, now.” Pops Staples wasn’t playing guitar. Instead, it was the young white guitarist Eddie Hinton. But Hinton idolized Pops, and he was trying to play as much like Pops as possible. (And when the Staple singers played live, Pops played the solo, so Mavis didn’t have to change what she sang during the shows.)

“I’ll Take You There” is also a great showcase for Mavis, mostly because she becomes a part of the band. For most of the song, she’s just ad-libbing, working with the groove. She’s casual and commanding, whooping and grunting but always staying in the pocket. Sometimes, she takes over, bringing the full force of her voice. Sometimes, she just sits back and enjoys what’s happening.

“I’ll Take You There” came out while the Civil Rights struggle was still raging, and after the assassinations of so many figures, including Staples family friend Martin Luther King, Jr. And yet it imagines a time, or a place, where things might get better, where “lying to the races” is a thing of the past. There’s a beautiful audacity in that image — the same beautiful audacity that has powered gospel music since before the advent of recorded sound. And while we’re still not there, we can hear some version of that imagined utopia in that groove.

GRADE: 9/10

BONUS BEATS: The reggae-influenced UK group General Public — led by veterans of ska second-wavers the English Beat — had a minor hit with a 1994 cover of “I’ll Take You There.” (It peaked at #22.) General Public covered the song for the soundtrack of the movie Threesome, and they tried to get as much of “The Liquidator” as possible back into the song. Here’s their video:

And here’s an absurdly young Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake covering the General Public version of the song on a 1994 episode of The Mickey Mouse Club, with Timberlake putting on a fake Jamaican accent to attempt dancehall toasting:

And here’s an absurdly young Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake covering the General Public version of the song on a 1994 episode of The Mickey Mouse Club, with Timberlake putting on a fake Jamaican accent to attempt dancehall toasting:

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here’s Big Daddy Kane’s 1998 take on “I’ll Take You There,” where producer Marley Marl scratches up Mavis Staples’ “daddy” ad-lib and Kane imagines a place where Ethiopians can eat in Red Lobster for free, and where war ain’t nothing but a game on Atari, and where fresh Gucci wear is only $5.99:

That’s my favorite example of a rap producer sampling “I’ll Take You There,” but there are so many others, especially from the early ’90s. Some examples:” – Stereogum.com