According to one of our preferred musical sources:

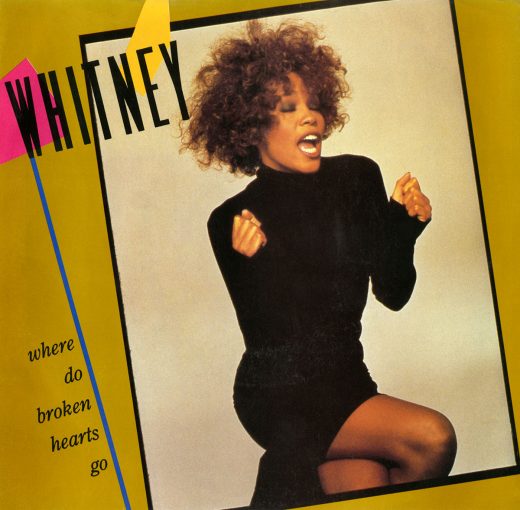

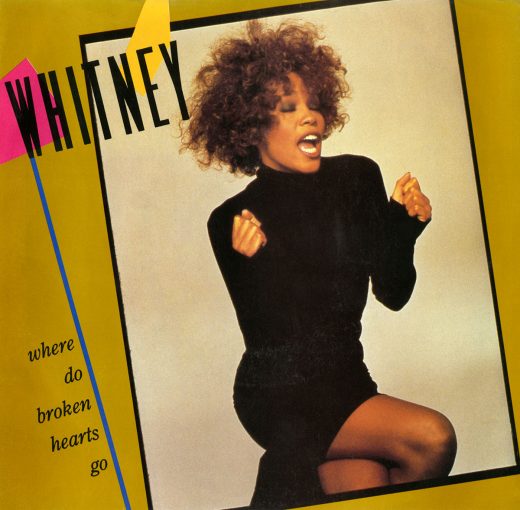

When Whitney Houston took her dance-pop single “So Emotional” to #1 in January of 1988, she hit a new benchmark. With that song, she became the third artist to send six singles in a row to #1. At that point, only the Beatles and the Bee Gees had accomplished that. A few months later, Houston outdid herself. When her grandly gloopy ballad “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” topped the Hot 100, Houston broke the record, becoming the only artist ever to rack up seven straight #1 hits. Today, that record stands. Given that “single” is now almost an obsolete category, that record will probably always belong to Whitney Houston.

There are caveats. In between “Saving All My Love For You” and “How Will I Know,” Arista released Houston’s album cut “Thinking About You” as a single. The label only pushed “Thinking About You” to R&B radio, not to pop stations. It reached #10 on the R&B chart and didn’t cross over to the Hot 100, which just goes to show how Arista boss Clive Davis was tightly overseeing Houston’s whole career. Davis had his eye on big, eye-popping chart records, and he wasn’t going to let a technicality like the existence of the “Thinking About You” single prevent him from trumpeting Whitney Houston’s grand achievement.

And it was a grand achievement. Four weeks before “Where Do Broken Hearts Go,” Michael Jackson’s “Man In The Mirror” topped the chart, making him the first artist ever to reach #1 four times in one album cycle. Almost immediately, Whitney Houston became the second. In the late ’80s, Houston was breathing rarefied pop air, reaching levels of crossover popularity that few in history have ever achieved. Arista may have been playing around with numbers, but the label didn’t manufacture Whitney Houston’s overwhelming popularity. That was genuine. Before long, all that success snapped back on Houston and sent her scrambling to rethink her whole public identity. Part of the problem was that she’d captured her big chart record with a song as drippy and boring as “Where Do Broken Hearts Go.”

Whitney Houston was not into “Where Do Broken Hearts Go.” In a 2000 interview, she said, “I didn’t want to do ‘Broken Hearts.’ I hated the song. I didn’t want to sing it. And [Clive Davis] actually literally told me, ‘You’re going to do the song. This song is your #1 song.’” Davis figured that the song was a hit, and Houston played ball. The song was one of many big-gesture Broadway-style ballads from Houston’s sophomore album Whitney. “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” wasn’t just a Broadway-style showstopper; it was a song that was mostly written by an actual Broadway guy.

Frank Wildhorn wrote songs for people like Natalie Cole and Kenny Rogers, but Wildhorn is mostly known for his work in musical theater. Wildhorn wrote or co-wrote productions like Jekyll & Hyde, Dracula: The Musical, and The Civil War. He co-wrote “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” with Chuck Jackson, who’d been a minor R&B star in the ’60s and who’d eventually turned to producing. (Jackson’s highest-charting single, 1962’s “Any Day Now,” peaked at #23.) Wildhorn and Jackson met while working on songs for a singer named Donna Washington, and they became writing partners, though Wildhorn claims most of the credit for “Where Do Broken Hearts Go.”

With “Where Do Broken Hearts Go,” Jackson gave Wildhorn the title, and Wildhorn claims that he wrote almost the entire song right then and there. In Fred Bronson’s Billboard Book Of Number 1 Hits, Wildhorn says that he wrote 90% of the song in 40 minutes and that Jackson came over that night so that the two could finish it up. (Neither Wildhorn nor Jackson ever wrote another #1 hit.) Wildhorn submitted the song to Clive Davis and rewrote the track to Davis’ specifications. Wildhorn says that other singers like Smokey Robinson were interested in recording “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” but that the songwriters held off on giving it out, waiting to see if it would make the cut for the Whitney Houston album. The waiting paid off.

If Whitney Houston thought that “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” was meaningless schmaltz, she wasn’t really wrong. Houston’s narrator spends the song pleading for an ex to come back: “We said we needed space/ But all we found was an empty place/ And the only thing I learned is that I need you desperately.” By the end of the song, Houston has tested out her hypothesis successfully: If somebody loves you, then they always love you. She’s back together with this person, and her musical has a happy ending. We never really learn where broken hearts go, but we do find out that they find their way home, back to the open arms of a love that’s waiting there.

Like so many of Houston’s other early-career ballads, “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” mostly exists to move Houston from one howling climax to the next. As ever, Houston does exemplary work, conveying regret and longing without fully diving into either. She builds assuredly from dramatically wistful verses to explosive choruses, and she hits all her marks. Houston knew how to work within this formula, but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s a formula. For all her professionalism, Houston doesn’t fully sell the song — mostly because there’s just not enough there to be sold.

Houston recorded “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” with producer Narada Michael Walden, who’d done all of Houston’s big dance-pop hits. (The session musicians who play on the song are Walden’s usual crew, including synth-bassist and future American Idol judge Randy Jackson. These days, weirdly, Walden and Jackson are bandmates in Journey.) Walden was an uptempo specialist, and “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” doesn’t give him much room to flex his thumping big-’80s style. Instead, the song has all the same weeping strings and watery keyboards as every other Whitney Houston ballad. There are some cool little drippy-faucet synth sounds in there, but those little flourishes aren’t enough to make “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” stand out. It’s simply one more inert mid-tier Whitney Houston ballad. For the moment, that was what America wanted from her.

For the “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” video, Houston worked once again with director Peter Israelson, her collaborator for the generally-similar “Greatest Love Of All” video. The clip’s narrative is pure cliché; it opens, for instance, with a scene of Houston getting dumped via flower delivery. But Houston is stunning in the clip, and she’s got a ton of presence. She looks like a movie star, which is what she briefly became. Israelson later claimed that the video convinced Kevin Costner that Houston was right for The Bodyguard.

After the final triumph of “Where Do Broken Hearts Go,” Houston released one more single from Whitney. Houston didn’t make a video for “Love Will Save The Day,” an uptempo club track produced by Madonna collaborator Jellybean Benitez, but the track still peaked at #9. (It’s a 7.) Houston spent much of 1988 touring. She sang at Nelson Mandela’s 70th-birthday celebration at Wembley Stadium, when Mandela was still locked up in a South African prison, and she recorded “One Moment In Time,” which became the theme song for NBC’s coverage of the Summer Olympics. (“One Moment In Time,” released as a standalone single, peaked at #5. It’s a 6.)

But the R&B audience that first embraced Houston was starting to feel left behind. At the 1988 Soul Train Awards, Houston’s name got a muted reaction everytime anybody read it. A year later, when the Soul Train Awards nominated “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” for Best R&B/Urban Contemporary Single – Female, the audience outright booed Houston’s name, even though the song had been a #2 hit on the R&B chart. Talking to Ebony in 1991, Houston bristled at the idea that she’d been catering to white audiences: “They had just gotten sick of me and just didn’t want me to win another awards. No, it does not make you feel good. I don’t like it and I don’t appreciate it, but I just kind of write it off as ignorance.”

But Houston did not write it off. Instead, Houston took those boos seriously, and she rethought her whole approach, moving away from crossover adult-contemporary audiences and steering straight into R&B in the years ahead. The 1989 Soul Train Awards would prove momentous in Houston’s career; it was also the night that she met Bobby Brown, her future husband. We’ll soon see Bobby Brown in this column. Before long, we’ll see Whitney Houston again, too.

GRADE: 4/10 – stereogum.com